Rainbow Tables

To most of you the term "rainbow table" is probably familiar. You are probably aware that they are used to aid the reversing of one-way hashes, usually when trying to crack a password. I personally think that they are a nifty little hack, and so I'd like to explain a little about how they are implemented.

Back to Square One

When storing a password, any developer worth their salt is going to hash it using a one-way hashing function. This lets them check that a given password is valid, without risking the possibility that someone could steal their user's passwords plain text passwords cough.

Of course, if that was a foolproof method of protecting passwords then this would be a very short post. If you do happen to find yourself in possession of a hashed password and you want to recover the plain text password then you need to figure our how to crack it. You can't reverse a hash but you can try and search for a text string that produces an identical hash. The obvious method of attacking a password hash is a brute force attack. You can generate a list of every possible password and hash each until you have output that matches you hashed password.

The simplicity of this solution is defeated by the fact that you are going to be trying a lot of combinations to find your target. Say you're searching for a five character password containing lowercase letters only. A naïve search is going to produce 26^5 possibilities. That's 11,881,376 tests to find a very trivial password. Even if you are testing thousands of hashes a second it could take hours to find a match. If you're clever then you'll prepare a collection of passwords that require cracking so you can process them all at once. One sweep through all possible passwords will be enough to complete your entire collection.

This reuse of generated hashes leads us to the next obvious improvement; what if we save all possible passwords and hashes in a table and just do a quick lookup whenever we have a hash to check? This seems like an ideal solution at first glance, however when you look more deeply you'll begin to appreciate exactly how much memory this would require. Each password is 5 bytes and its associated MD5 hash is 16 bytes. The minimum storage required for a naïve lookup table is (16 + 5) bytes x 11,881,376 possibilities. That's 200MB. Don't forget that we're talking about 5 letter passwords here. Any increase in complexity (either in length or possible characters) increases the size requirements exponentially. To crack a secure password would require petabytes of storage for our table. Storing and searching that data efficiently becomes a whole new problem (Google has managed to inadvertently solve this problem).

So there you have it, the two problems we face are time and memory. What we need is a compromise. Wouldn't it be fantastic if we could only store every thousandth hash, and extrapolate from there? The most obvious problem with that is that hashes are evenly distributed. Two passwords that vary by a single letter produce hashes that are as different as passwords that are completely different. So as it becomes difficult to use the hash/plain text passwords pairs we know to crack hashes we aren't storing a plain text value for. Rainbow tables get around this in an interesting way.

The Basic Principle

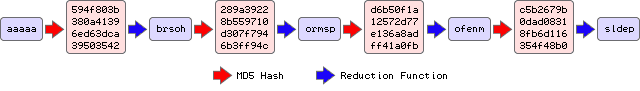

A rainbow table consists of many chains of alternating hashes and passwords. A single chain may look something like this.

A rainbow table will consist of thousands of these chains. The memory saving comes from the fact that we only ever store the start and end points of a chain; we can easily regenerate the rest of the chain when we need it.

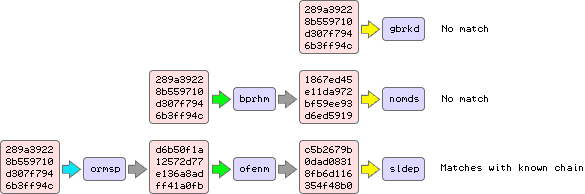

So how does having these chains actually help us? That's easy. We need to find the chain that contains the hash we are searching for. Let's say that the hash we are trying to reverse is "289a39228b559710d307f7946b3ff94c" - the second hash in the example chain above. We take our hash, and start creating a new chain:"ormsp", "d6b50f1a12572d77e136a8adff41a0fb", etc. At each step, we check whether we have created a link that matches the end point of a pre-calculated chain (in this case looking for 'sldep"). When we do find a match, we know we've found a chain that contains our password.

Our work is not done yet though. We take the chain we just found and start populating it from "aaaaa" onwards. Once complete we have a complete chain of hashes and passwords in memory, and we can now travel backwards from our original hash to see that our password is "brsoh" (anyone with the password of "brsoh" is advised to change it now - it's wasn't a very good password anyway).

The only missing piece now is knowing how we determine that the step immediately after "96948aad3fcae80c08a35c9b5958cd89'should be "ormsp"? The answer to that is that there is nothing special about that value. We can use any algorithm that takes a 16 byte input (the hash) and generates a 5 letter passwords. This is our reduction function. The implementation is irrelevant as long as it consistently generates 5 letter plain text words when given a hash value as input.

So that is essentially the magic of rainbow tables. They're both elegant and simple. There are a few minor details that I've skipped for now. They deal with a few problems that arise from implementation described above.

Coverage

The first problem is that a rainbow table can't guarantee that it contains every single possible password. The output of our reduction function is evenly distributed across all possible passwords. Once our rainbow table contains 90% of all of possible plain text passwords, anything the reduction function outputs has a 90% chance of being a duplicate password. The more chains we generate, the more duplicates and the more wasted memory we get. The problem becomes exponentially worse as you attempt to increase coverage. There has to be a point at which you say enough is enough and live with the trade-off between the coverage you have and the memory your rainbow tables occupies.

Collisions

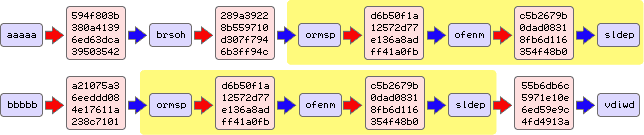

The second problem is related to the first. When we are generating chain and we create a plain text password that already exists in another chain, we are going to start following the same path as the other chain. This is referred to as merging.

Note how the two yellow sections are identical for two chains with completely separate starting points.

This is a big problem because, as stated before, the chances of reduplicating a password are very high. We will have entire chains that are almost identical to other chains. That leads to a huge waste of space. We could even end up generating the same password within a single chain, leading to an infinite loop.

We can do checks for loops, but that would add extra complexity to the code.

Solving Merging

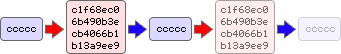

Following on from the elegance of the main algorithm, the solution for merging and loops is very simple. It is also what separate rainbow tables from other cracking algorithms that use chains. What rainbow tables do is use a different reduction function for each step of the chain.

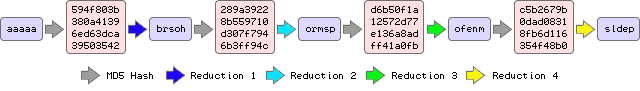

The above illustration should give you a hint at why rainbow tables are so named.

This approach completely eliminates loops because a reduction function is never reused in the same chain. It will also cut down on merging between two chains because if the merging occurs at different steps in the chains (which is most of the time) the different reduction functions let the chains diverge naturally.

The differences between reductions function doesn't even have to be very large. It just has to be enough that two reduction functions with the same input will output two different passwords.

Adjusting the Cracking Stage

The change will mean that our cracking stage needs a little adjustment. We will need to test the hash we are trying to crack against each possible reduction function. To do this we'll need to ensure that there are fixed number of steps in each chain. We then pick a step to build from and complete the chain. For efficiency we work from the very last reduction function to the first.

Note how the output of the reduction function changes even though we are using the same input.

Do You Want to Know More?

Co there you have it. Everything there is to know about rainbow tables. They're nothing new, but their implementation is something that should be simple enough for any programmer to understand and appreciate. If you're looking for more information then the following links may help you out.

- The mandatory Wikipedia link for those who want more technical details.

- Jeff Atwood tries out some available packaged rainbow tables and gives some misguided advice on protecting your passwords.

- Thomas Ptacek has written a great post on how you can really protect your passwords. Basically his advice boils down to "don't write your own security algorithms".

- RainbowCrack is an general Rainbow Table implentation, and the source is available for download.

- Martin Hellman originally proposed the idea of a time-memory trade-off for password cracking in 1982.

- The fantastic photo at the top of the post kindly released under the creative commons by Proggie.